Bad Movies: Are You Watching them Wrong? (Part One)

I recently spent several days convinced I had a brain tumor.

I’ll give a spoiler for everyone who needs to know, before going to the movie, whether the dog dies or not – I’m fine. I don’t want to stress anyone out with unresolved medical news. I’ve been having some migraine-adjacent symptoms, but whatever else may be going on, my brain is clean as a whistle. No hemorrhages, lesions, or tumors to be seen, just beautiful rolling hills of gross gray brain goo.

My brain stem worries stemmed from my brain – specifically the anxious, controlling part that decided to look at the MRI images on my own and then spend hours comparing those photos to “abnormal” brain scans online. It reached the point where I had started gazing wistfully at Audrey, thinking “Will she be okay once I’m gone?” (The answer: sure.) or staring at the cats thinking “The boys will grow old without me,” and then I’d start getting misty, because there’s nothing that will make me teary-eyed faster than an absolutely maudlin made-up fantasy centering around myself. I don’t know exactly what that says about me, but it ain’t pretty.

Anyway, my current best guess as to what’s actually going on is that I’m getting these mild, neurological-feeling disturbances due to cervical spine issues (confirmed by a previous MRI, and not another hypochondriac fantasia of mine), which seems like a reasonable thesis, except you all saw how badly I fucked up the MRI thing, so don’t hire me as your doctor.

I laugh now, but I was getting incredibly stressed and depressed for a while, because I was absolutely convinced my brain was getting eaten – to the point that I began attributing things like my mood swings to my nonexistent tumor, even though (1) I’ve had mood swings all my life, and (2) if I need a medical explanation for my moodiness, I don’t need a tumor. I already have some perfectly good ADHD at home! What a heady mix of attribution and confirmation biases I’d made for myself!

Somewhat similarly, during the period I suspected my neurodivergence was autism spectrum disorder, my natural dislike of loudness and crowds increased to fit my presumed brain chemistry narrative (it’s a problem for ADHDers, too, of course, but I didn’t know that then), a shift which doesn’t even make sense. Whether or not I was diagnosed, my reactions should have been the same, but they seemed to edge upward just slightly.

But these instances of twisting my symptoms to fit my fears got me thinking about how much the narratives we tell ourselves matter. Expectations matter. Which leads me, in a somewhat roundabout way, to some feelings I have about “bad” movies, as well as a confession:

I am not, in point of fact, a hater.

I guess you were expecting something juicer. The only reason my non-haterdom qualifies as a confession, is that it might sound odd coming from me, specifically, as one of the hosts of a long-running bad movie podcast. A huge part of my livelihood involves laughing at failed films, and if you don’t think that occasionally gnaws at me, causing me to wonder if I’m just a parasite who feed not by sucking blood from cats, but Cats (2019, dir. Tom Hooper), then you’re woefully mistaken. Or probably not that woeful. Your viewpoint on me likely won’t change your general woe quotient, but people not liking me certainly makes me woeful, and then I have to go watch Cats (2019, dir. Tom Hooper) to cheer up.

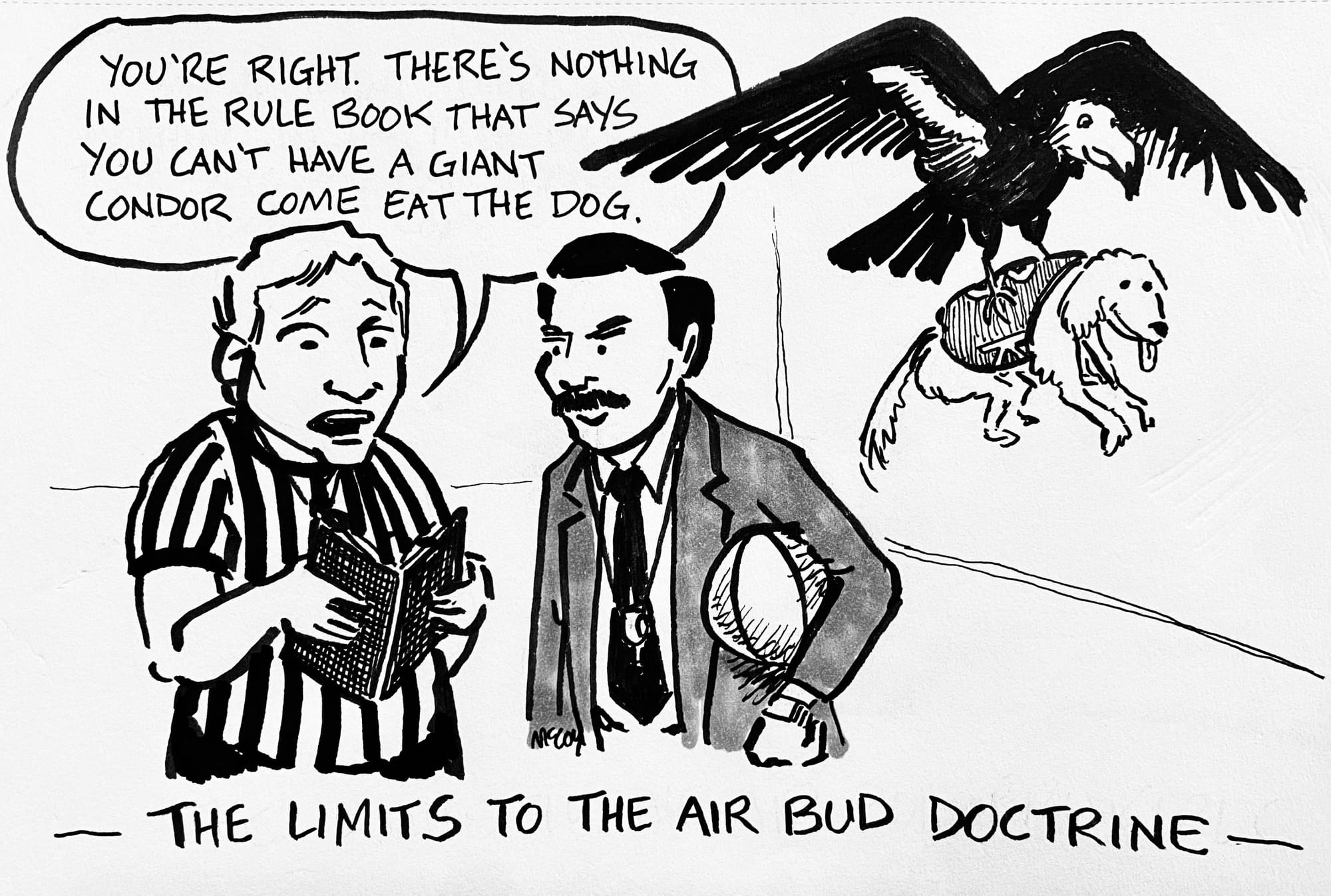

In its broad outlines, the podcast half of my career seems insufferably snarky. But I hate snark. Snark is one of the great internet diseases, along with trolling, the devaluation of creative work, and, of course, digital leprosy. Snark is dismissiveness disguised as wit. It’s experiencing art with the assumption that you’re smarter than the makers, grasping at anything that confirms your biases, and then running out the door to make a 16-minute YouTube video about all the “plot holes” you saw. (BTW, internet – just because something isn’t explained, doesn’t make it a “hole.” Films often foolishly assume you’re smart enough to fill some gaps on your own. Movies don’t operate on Air Bud logic, where you have to expressly say everything, lest you get a dog playing basketball. Well… except the movie Air Bud. That one does operate on Air Bud logic.)

While I may have a perverse interest in the stuff society has labeled “bad,” I’m always hoping to like something. Just as you shouldn’t meet a new person with the attitude, “I can’t wait to hear what dumb things this fuckin' goober's gonna say,” you probably shouldn’t walk into a movie already assuming it’s shit.

When you operate that way, you might miss what a film is actually doing in a wild rush to have your biases confirmed. Critics in 1997 panned Starship Troopers, claiming it was cheerfully fascist, without thinking that maybe the cheerful fascism was the point. Perhaps a man who grew up in Nazi-occupied Netherlands might have had something up his sleeve when he clothed a bunch of fresh-faced teens, including TV’s Doogie Howser, in SS garb. The culture eventually caught up to the satire, but the level of initial misunderstanding was shocking, and I think it largely came from a snobbish assumption that a movie about a bunch of space bugs exploding into goo couldn’t possibly have subtext.

So why not tack the other way? When you view a film with generosity of spirit, you’ll have more fun. Who are you trying to impress by proving that you’re smarter than the Vanilla Ice vehicle Cool as Ice? I mean, these days, Mr. Ice is announcing his line of specialty lighting fixtures at Florida boat shows. What's the point? You’ve already won.

Lately I’ve wondered if my fascination with the outré is an extension of my feelings about the odd and misunderstood. Since neurodivergence is one this newsletter’s recurring themes, I should probably mention that I struggle with something that’s common to a lot of folks with ADHD – “Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria.”

To borrow some bullet points from WebMD, people with RSD are likely to:

- Be strong people-pleasers

- Feel more embarrassed or self-conscious

- Have low self-esteem and self-doubt

- Display sudden outbursts of physical emotions like anger, tears, and sadness

- Engage in negative self-talk

- Have difficulty managing their reactions

- Find it draining to manage relationships

- Suddenly become quiet, moody, or show signs of depression or anxious feelings

That’s right! I’m a hit at parties! Please invite me, so I won’t come!

What does this have to do with movies? Well, I think I’m generally kind of a soft touch. Despite those bullet points that highlight some of my more prickly characteristics, I think I’m a fairly understanding person when it comes to the myriad ways people exist in the world. I say live and let live, because that’s the grace I would prefer people to extend to me. As a result, I have more than my share of friends that might also be considered “odd” or “difficult” by some, but we live happily together on our island of misfit toys.

Thus, though it might be an odd fallacy to treat non-living things with the same care, I feel a similar affection for misbegotten art, which often feels (to me) like the threadbare-but-still-standing twig Charlie Brown brings to his Christmas pageant. In the words of Linus, wisest of the Peanuts characters, “I never thought it was such a bad little tree. It’s not bad at all, really. It just needs a little love.

In that spirit, I’d like to suggest some other ways to engage with “bad” movies. Please, laugh at the stuff that’s funny. But if you follow my lead, perhaps that laughter will ring with a warm appreciation of the ridiculous, and you’ll feel more bighearted, and less like getting jollies by pushing a three-legged puppy down the stairs.

BAD MOVIES: SOME WAYS TO WATCH

→ As surrealism ←

The first time I attempted to watch the film Love on a Leash (2011, dir. Fen Tian), I was certain my TV was broken.

There was no sound. I don’t mean “bad” sound, or low sound, or music-but-no-words sound. I mean void. Absence. The nothingness from The Neverending Story. I mean “check all the cables, restart everything, sigh, and then log onto Amazon to price check new sound bars.”

Then a dog started talking.

Let me back up. If you haven’t worked in film or TV production, you may not be familiar with the concept of “room tone.” If so, let’s try an experiment. Take a moment to stop reading this newsletter aloud to the sick orphans you mentor, and just listen. Even in a “quiet” room, you can hear something: birds chirping, the hum of your refrigerator, car engines on a far off street, or your upstairs neighbor vacuuming up those chirping birds (weird dude; consider moving?).

That ambient noise is room tone. When making a movie, the sound person takes a few extra minutes at the end of each scene to tell everyone to shut up so they can record what is, essentially, nothing. Films need that aural wallpaper for editing later, to smooth over cuts and give an auditory sense of the space. Without room tone, a scene without dialogue doesn’t make you think, “This is a quiet scene.” You think, “Oh shit. MY EARS!”

Love on a Leash dares to make the avant-garde choice to eliminate all audio whenever someone’s not actively talking, over its full 90 minute runtime, and it’s disorienting as hell. But making you doubt your own senses is just the first in a smorgasbord of confusions. There’s also the plot. Specifically, Love on a Leash is about a woman who finds love with a stray dog who magically becomes a man whenever the sun sets. This Mr. D. Oggman spews constant voiceover while in dog form, and that voiceover is clearly provided by a different actor than the one who plays him as a human. This second dog actor (or “dactor”) has clearly not read the script. Instead, the voiceover dog feels like he wandered in from another movie, glanced at the poster, and said “Dog comedy. Got it. Let’s go! Time is bones! And bones is money, according to an I Think You Should Leave sketch I once saw. Arf!” While the human stuff is all bittersweet romance, the dog voiceover is a constant stream of improvised off-color jokes, like outtakes from America’s Doggiest Home Vide-dogs: Doin' it Doggystyle.

When presented with such a discombobulating stew, you can either throw up your hands or you can embrace it. After all, if disorientation isn’t at least a little fun, drugs wouldn’t exist. So why not take a more philosophical tack, and appreciate these elements as if they were artistic choices? Enjoy the way the technical issues make you hyper-aware of the artifice of filmmaking, in a way that’s as distancing as any Brecht play. Good dog!

→ As cultural artifact ←

Lots of bad movies are based on fads, which makes sense. If you lack money or skill, hitching your wagon to the zeitgeist is a great way to compensate for both, because theoretically you know you’ve got a built-in audience of… I dunno… people who love disco roller rinks? (Roller Boogie, 1978, dir. Mark L Lester)

Fad movies tend to be bad movies because they’re the purest distillation of a cash-grab mentality. No one involved in greenlighting The Emoji Movie (2017, dir. Tony Leondis) was like, “Think of the artistic and character opportunities this source material provides!” It was more like, “Cha-ching! Emojis are in the public domain! That makes me feel [emoji of eyes with dollar signs]!”

This road leads you to strange showbiz bedfellows like Rod Amateau (a writer-director who cut his teeth in classic TV with George Burns and Gracie Allen) employing little people in grotesque animatronic suits to play characters named “Valerie Vomit,” “Ali Gator,” and “Messy Nessie,” for 1987’s The Garbage Pail Kids Movie; or a young Brooke Shields playing a 13 year-old pinball hustler in Tilt (dir. Rudy Durand) – a film that had the misfortune to come out in 1979, the last possible moment anyone gave a shit about pinball.

These movies offer a very particular snapshot of the time. On release, they were easy to dismiss as crass trend-chasing. So what? Yesterday’s cash-ins are today’s fascinating historical artifacts – and if something initially thought to be a fad endures, it can be even more fun to see how Hollywood perceived it back in the day.

Take Joysticks (1983), directed by Greydon Clark (a true schlock auteur, responsible for many delightful bad movies, including 1990’s equally fad-tastic Lambada movie, The Forbidden Dance, and 1987’s Uninvited, about a boat trip ruined by a cat with a smaller, meaner, mutant cat inside its mouth). Joysticks is about video games, and it’s kind of beautiful how transparent it is about its mercenary origins. Like the titular owner of Noah’s Arcade in Wayne’s World, who cheerfully admits he doesn’t care about games so much as taking quarters from teens, Clark clearly just needed a zeitgeisty location to put some boobs. He figured, “Arcades are big!” without ever stopping to think whether they’re a place where babes hang out topless. Cultural artifacts can fun for what they get right, and even more fun for the (many) things these fading showbiz pros get wrong.

→ As a chance to see people and places that aren’t always represented in media ←

Most big movies are made in Hollywood. Unless they star Iron Man or Madea, then they’re from Atlanta. Plus I guess some are made in New York... Unless they’re set in New York, and then they’re probably made in Vancouver, and Jackie Chan is fighting Bronx gang members against NYC’s beautiful snow-capped mountains.

Let’s just agree that films tend to be shot in a relatively small number of places. Even if a movie says it takes place in Dubuque, it’s a Hollywood Dubuque that looks an awful lot like Pasadena, filled with lithe, tan, surgically-enhanced Iowans, healthy and aglow from their morning ginger shots and fair trade poke bowls.

It's the micro-budget films that end up getting made elsewhere. Oddball filmmakers working outside the system often just end up shooting in their hometowns, which are usually locations not found in mainstream films. This makes “bad” movies a gold mine if you’re tired of seeing the same twelve L.A. buildings ad nauseum. Instead you get to see how the other half lives/lived in other parts of the country.

Take a regional horror movie like Fiend (1980, dir. Don Dohler). You watch it, and perhaps you don’t have any idea what’s going on, or why, or which of the two men with giant black handlebar mustaches is the good guy and which is the titular fiend. But you do get a nice long look at Don Dohler’s suburban 1980 Maryland cul-de-sac, backyard, and basement rec room, complete with only the woodiest of wood panelling.

Perhaps you say, “But Dan. I seek thrills. Why would I want an inert, regional horror film with Solaris-slow shots of a 1980 suburban Maryland subdivision?” For the same reason everyone was briefly excited, during covid, to get Zoom-powered peeks into their co-workers' homes. Nosiness! Also retro chic! If you subscribe to twelve different Instagram feeds showing you ugly wallpaper from the late 70’s, then regional low budget films might be right for you!

→ As creative therapy ←

I’ve never made a movie, and only appeared in a couple of tiny cameos; but I have made my career in various forms of entertainment. Perhaps those experiences have made my perception of “bad” media a little different than if I were, I dunno… what’s a normal job? Crossing guard? Accountant? Carhop? Do they still have those? Are they hiring?

I’ll still laugh when something goes wrong, or a special effect looks especially janky, or someone’s line reading goes beyond inept into a zone where it seems like the entire concept of language was explained to them via a crumpled pamphlet that fell through a black hole from another galaxy.

I’ll laugh, but with a different tone. It’s laughter with the subtext “there but for the grace of God go I.” It’s a knowing laugh that says, “Yes. Of course. Of course that would go wrong. Of course it would look that way. Of course the CGI evokes an old Listerine commercial. Of course John Travolta’s wig looks like he constructed it from what he could rescue from the drain trap in Danny DeVito’s shower. Of course, of course, of course.

Here’s a not-so-secret secret: It’s hard to make entertainment. Failure happens to the most talented among us with startling frequency, and failure is not only impossible to avoid, but it’s economically infeasible to do so. Film is art, but it’s also a job, and sometimes you just need to stack cash.

American actors try to pretend this isn’t the case, and that they’re REALLY EXCITED to be appearing in Sonic the Hedeghog 2 because of their deep personal connection to video games about fast spiky things, but British actors are delightfully open about the need to be mercenary – I often think of Michael Caine’s quote about Jaws: The Revenge (1987, dir. Joseph Sargent): “I have never seen it, but by all accounts it is terrible. However, I have seen the house that it built, and it is terrific.”

Industry folks understand this attitude, even if some pretend they’re above it, but it can be confusing for viewers – “Why is this talented celebrity wasting their time with this crap?” they think. And the answer is simple: it’s a job.

Oh sure, most folks want the job to be good too, if they can swing it. Maybe the movie they’re in started out fine, but got messed up. Maybe it started out bad, but they thought “Eh, I might be able to salvage something.” Maybe they wanted to work with someone they admired, or were told it would be good for their career, or maybe they knew the project was bad, but took it anyway, because the offers weren’t coming. Or maybe, again, it’s a damn job. Creators and craftspeople can’t control everything, and it’s honestly kind of weird that we hold them artistically responsible for each turn of their careers. No one’s ever like, “Well, you’re doing great as the general manager of Applebees, but what of the pure work you did at Jack in the Box? That was the visionary frying of a true cholesterol artiste.”

Anyway, have a good laugh. But as a co-conspirator, not a superior. We’ve all had a shitty job. It can be therapeutic to see even the most glamorous struggle.

→ As inspiration ←

Very few movies are 100% bad. Genuinely clever, innovative, or affecting morsels can pop up in otherwise baffling or incompetent films, and finding them can feel extra special, like you’re a treasure hunter, panning for gold up on schlock creek. These special moments feel all the sweeter for showing up in such unpromising places – like how a pearl gets some of its beauty from the knowledge that nature built it from sand and bivalve goo.

Some examples:

- Dungeons & Dragons (2000, dir. Courtney Solomon) is a mess, but it has Jeremy Irons and Rocky Horror’s Richard O’Brien chewing the scenery like famished British termites with pica.

- 2019’s Serenity, from writer-director Stephen Knight has hothouse tropical noir vibes to spare, and an admirable commitment to completely untenable material.

- 1984’s Monster Dog from bad movie all-star Claudio Fragasso (Troll 2) is mostly a snooze, but it’s got some tremendous music from Alice Cooper.

- Heartbeeps (1981, dir. Alan Arkush) may have a disastrous performance from Andy Kaufman as a robot with an world-record irritating voice, but it also has fascinating makeup from Stan Winston and a score by John Williams.

- Vanilla Ice’s aforementioned 1991 star vehicle Cool as Ice (dir. David Kellogg) has colorful, dreamy photography from multiple Academy Award winner Janusz Kaminski (Schindler's List? Saving Private Ryan? MAYBE YOU’VE HEARD OF THOSE?)

If you’re a creative person, and you see the seeds of a good idea choked off by the weeds of the film around it? Consider re-potting it in your own work, with your own spin. Art has always inspired other art, and there’s no reason you have to find that inspiration in good art. Quentin Tarantino has been mining the best parts of not-so-great movies for years, and it’s certainly worked out for him. So you can steal stuff too! Plot, that is. You probably can’t steal acclaimed Polish cinematographer Janusz Kaminski. Legally speaking, that’s kidnapping.

This is awfully long for a newsletter already, but I’m only half done, so look for part two next time! In the meantime, happy viewing!

For earlier posts, check out the archive. In my other life, I’m a podcaster. Listen to my show The Flop House, here. In my other other life, I’m an Emmy-winning comedy writer, currently unstaffed. If you’re looking to hire, get in touch!